Dingo effects on ecosystem visible from space

Satellite images taken over three decades show that keeping dingoes out comes at a price.

Satellite images taken over three decades show that keeping dingoes out comes at a price.

The environmental impacts of removing dingoes from the landscape are visible from space, a new UNSW Sydney study shows.

The study, recently published in Landscape Ecology, pairs 32 years’ worth of satellite imagery with site-based field research on both sides of the Dingo Fence in the Strzelecki Desert.

The researchers found that vegetation inside the fence – that is, areas without dingoes – had poorer long-term growth than vegetation in areas with dingoes.

“Dingoes indirectly affect vegetation by controlling numbers of kangaroos and small mammals,” says Professor Mike Letnic, senior author of the study and researcher at UNSW’s Centre for Ecosystem Science.

Apex predators an play important role in maintaining the biodiversity of an ecosystem. Photo: Nick Chu.

“When dingoes are removed, kangaroo numbers increase, which can lead to overgrazing. This has follow-on effects to the entire ecosystem.”

The Dingo Fence, which spans across parts of Queensland, NSW and South Australia, was erected in the 1880s to keep dingoes away from livestock. At 5600 kilometres long, it’s one of the longest structures in the world.

Up until now, most dingo research has been site-based or conducted using drone imagery. But NASA and United States Geological Survey’s Landsat program – which has been taking continuous images of the area since 1988 – has made landscape-wide analysis possible.

“The differences in grazing pressure on each side of the fence were so pronounced they could be seen from space,” says Prof. Letnic.

The satellite images were processed and analysed by Dr Adrian Fisher, a remote sensing specialist at UNSW Science and lead author of the study. He says the vegetation’s response to rainfall is one of the key differences between areas with, and without, dingoes.

“Vegetation only grows after rainfall, which is sporadic in the desert,” says Dr Fisher.

“While rainfall caused vegetation to grow on both sides of the fence, we found that vegetation in areas without dingoes didn’t grow as much – or cover as much land – as areas outside the fence.”

This 32-year time lapse shows the difference in vegetation on both sides of the Dingo Fence – and, if you look closely, the NSW state border can be seen from space. The satellite images have been converted to show non-green vegetation cover, like shrubs and dry grasses, which are an important part of vegetation in desert landscapes. Sections in white are either from clouds or missing data. Video: UNSW Sydney / Adrian Fisher.

Apex predators play an important role in maintaining the biodiversity of an ecosystem.

Removing them from an area can trigger a domino effect for the rest of the ecosystem – a process called trophic cascade.

For example, an increase in kangaroo populations can lead to overgrazing, which in turn reduces vegetation and damages the quality of the soil. Less vegetation can hinder the survival of smaller animals, like the critically endangered Plains Wanderer.

Changes to vegetation triggered by the removal of dingoes have also been shown to reshape the desert landscape by altering wind flow and sand movement.

“The removal of apex predators can have far-reaching effects on ecosystems that manifest across very large areas,” says Prof. Letnic. “These effects have often gone unnoticed because large predators were removed from many places a long time ago.

“The Australian dingo fence – which is a sharp divide between dingo and non-dingo areas – is a rare opportunity to observe the indirect role of an apex predator.”

The 5600 kilometres long Dingo Fence is one of the longest structures in the world. Photo: Mike Letnic.

Satellite imagery traditionally only looks at photosynthesizing vegetation – that is, plants, trees and grass that are visibly green.

But the researchers used a model to factor in non-green vegetation, like shrubs, dry grasses, twigs, branches and leaf litter.

“Non-photosynthesizing vegetation has a different reflectance spectrum to photosynthesizing vegetation,” says Dr Fisher.

“By using the satellite image and a calibrated scientific model, we were able to estimate the non-green vegetation cover – which is especially important when studying a desert landscape.” The model was developed by the Joint Remote Sensing Research Program, a collaborative group that includes UNSW.

While there are other contributing factors to the difference in vegetation – for example, differing rainfall patterns and land use – the satellite imagery and site analysis showed dingoes played a central role.

“There were clear differences in landscape on either side of the dingo fence,” says Dr Fisher. “Dingoes may not be the whole explanation, but they are a key part of it.”

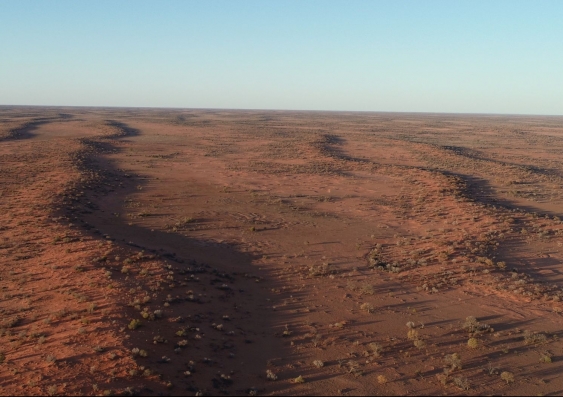

A drone view of the Strzelecki Desert shows sand dunes dominated by shrubs and trees, and swales dominated by grasses. Photo: Adrian Fisher.

Satellite image technology is a powerful tool for assessing large-scale role of not only dingoes, but all kinds of environmental change.

In 2019, researchers from UNSW Engineering used powerful satellite radar imaging technology to map severe floods in near real-time – intelligence that could help emergency services make tactical decisions during extreme weather events.

Dr Fisher hopes to next use Landsat imagery – which is freely available to download – to study how different amounts of vegetation can influence bushfire frequency.

“Our study is an example of how satellite technology can be used in big picture environmental research,” says Dr Fisher.

“With over three decades’ worth of data, this technology has opened up so many research possibilities.”