The UNSW textile designer and associate lecturer makes fabrics with local resonance to promote a more sustainable way of living.

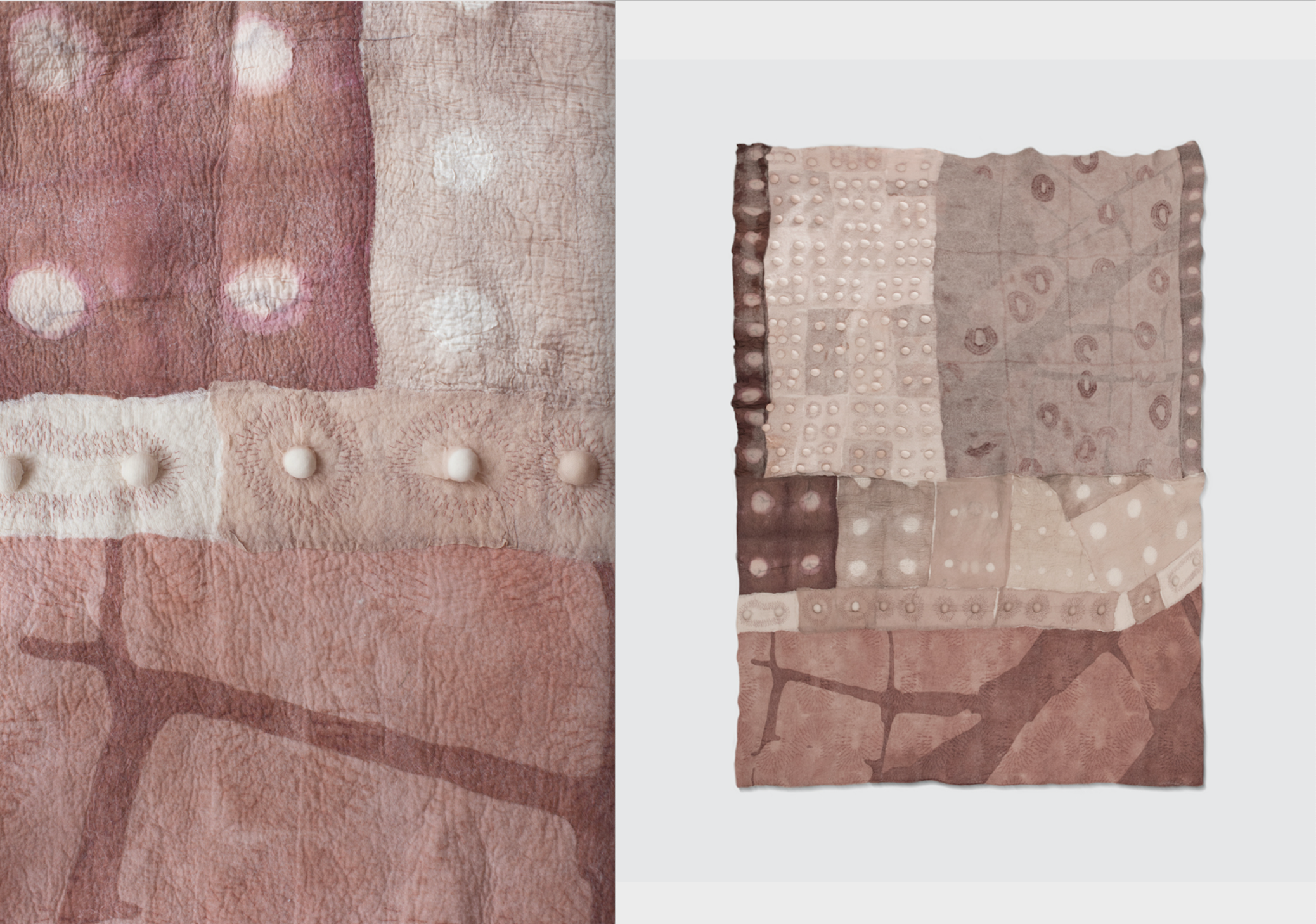

Earthy, sensual and evocative, Emma Peters’ textiles engage the emotions. Finely crafted from silk, organic cotton and merino wool, her work maps landscapes: the literal, the metaphorical and those of the human body.

Her textiles are a meditation on her place in the world as a non-Indigenous Australian. “I sit in a space between design and art where ideas and concepts come first. I reflect on these through the making,” the designer, educator and maker from UNSW School of Art & Design says.

Her pieces acknowledge that we are “surrounded by incredible nature that is only here because of the care Australia’s Indigenous custodians have taken of the land for thousands of years ”, she says.

Influenced by an early rebellion

Growing up one of four sisters, her family home was boisterous and supportive. Her parents fostered creativity and independent thinking. And yet it was a childhood rebellion of sorts that ignited her love affair with textiles.

“Most kids come to textiles with [a] basic kind of introduction to making but my mum was pretty adamant that I shouldn't learn how to sew. It was against her feminist grain,” she says.

“So I learnt because I had to – [I] remember having to hem up my skirt for school … on reflection, it was an empowering moment. I'm just going do it myself. I'm capable. And I can do it.”

The thrill of being able to fix something for herself would ripen into a long-term passion for sustainability, repair and reuse. Today her textile practice pivots around upcycling, slow stitch and natural dye, working within the principles of a circular economy.

Inspiring emotional attachments

Through a focus on the handmade, Ms Peters’ work cultivates a visceral connection with the user. Developing deeper relationships with objects helps combat the commercial imperative to ‘bin it and buy a new one’, she says.

“We are currently in a space where we must educate ourselves in new ways of engaging with textiles without implicating the health of the environment and the lives of those that produce our cloth,” she says.

Her childhood on Sydney’s lower north shore was punctuated with time spent on her grandparents’ farm in the Riverina. The farm enriched her sense of place with its more languid pace, raw textures and “sense of freedom”.

“Looking outside your window and not seeing any houses… you’d feel like you’re on another planet actually. Because the ground was so red and cracked and it was so flat,” she says.

“[Whereas at home in] Turramurra – it’s like rainforest and we had a creek and tadpoles, and it was kind of dark because we were under canopies. It was a whole different life experience too.”

The farm also made her aware of her “privilege as a white woman living and working on stolen land”, she says; a realisation that has changed how she makes work.

“My grandfather was given the farm because he was a returned soldier. But who gave it? Whose was it to give?” she says. “It opened up this really interesting, unspoken conversation, particularly with my mum and I, about that idea of land-ownership, [with] the family farm existing on unceded Wiradjuri country, and the systemic, ongoing privileges that are generated from that perceived ownership…

“And how can I respectfully acknowledge and then create from it?”

Commerce, nature and her evolving aesthetic

After graduating with a Bachelor of Design from UNSW, Ms Peters worked in commercial homewares for almost fifteen years for iconic Australian brands including Sheridan and Julie Paterson’s Cloth Fabrics.As a print specialist and range stylist at Sheridan, she designed and collaborated with offshore teams to create and launch new ranges.

“Sheridan in particular were interested in designing with a visual Australian language, because that was their proposition and point of view for the international market, as well as the local,” she says.

“So nature was a big influence, alongside global textile trends: the Australian bush and the fauna and flora, the coastal element, that easy luxury lifestyle.”

Over time however concern for the ethics of practice became more significant for her: “I was concerned about what my impact was”, she says, and she returned to research.

Handmade pieces that evoke the personal

She moved back to creating bespoke pieces with her master’s degree, embracing craft and traditional textiles in parallel with contemporary technologies. The return to working by hand resonated with her, she says.

“There’s something about that slow, thoughtful making [process] – your hands are busy and you’re problem-solving, and the material guiding you through the process. Discoveries are made through that process that are quite surprising, whether it be perceived mistakes or intentional acts upon the material.”

Additionally, people recognise the care and craft in handmade objects, she says.

As part of her research, she created works inspired by memories: both her own and other people’s.

“I was looking at memory and what I was calling mnemonic textiles and trying to understand why these pieces like heirloom quilts and the things that we keep, [why] this is so different from the value we give something we buy from places like IKEA.”

Pairing the handmade with the personal created enduring relationships, she found. “[Memory] plays into identity as well – so [you respond to] things that reflect you and your evolving sense of self.”

Sustainability and celebrating self

With the pandemic, Ms Peters has become more conscious of the materials she uses. But the decision to “look towards my environment to make within this local context” remains informed by her personal memories.

“Wool is something I use a lot of, and that connects back to the farm and that experience I had as a kid … that smell and that tactility, that all comes into play,” she says.

She uses organic materials like eucalyptus, Morton bay figs, mangrove bark, cochineal, madder and logwood to create her earthy hues. And the slower pace of working by hand allows her to surrender to and celebrate each new creative landscape.

Her textile practice has also mapped her journey of self-discovery. The work Topology of Memory, for example, tracks terrains of the human body, a subconscious echo of her struggles with breastfeeding.

Each piece is a “sort of translation of your personal struggles into your art form, almost seamlessly occurring as well … and hand-stitching is rhythmical, like walking in a way. It's a way to journey through ideas.”