The retail industry is inherently easy to enter but that does not mean all business models are sustainable. Many retailers who succeed early on tend to expand too quickly to capitalise on their early success.

To name a few, once popular Adriano Zumbo, Jamie Oliver and most recently, George Calombaris’ company MAdE Establishment Group – have filed for voluntary administration due to financial difficulties.

To date, more than 160 stores have closed down and just last week – department store David Jones announced its half-year profits have fallen by more than 50 per cent.

Whether this will impact the wider industry remains debatable.

In Australia, department stores are not ‘destination’ retailers but depend heavily on mall traffic and ‘drop-in’ business.

“Mall operators in Australia are not anchored around department stores – their business models are instead often based around supermarkets,” says Professor Jack Cadeaux, Head of the School of Marketing at UNSW Business School.

“When you compare department stores to boutiques, department stores often do not have anything particularly unique. They have no unique value proposition. They replicate the brands' ranges sold in the brands’ own stand-alone stores. Is that creative merchandising?

“Given such product limitations, department stores could consider storewide promotions and seasonal events to make themselves more relevant to their market. However, as many others have said, this would have to be backed up with far better in-store service. Many Australian shoppers have visited overseas stores such as Isetan and Takashimaya in Singapore and know the difference very well.

“Another harsh reality is that consumers are fickle and want what is trending – younger consumers especially, tend to be less reliable. They are eager to line up for hours to try a new trend and move on to the next trend once the hype is gone,” says Professor Cadeaux.

What is the main problem that the industry is facing?

A key causal factor is the prominence of online retailing – a channel that Australian offline retailers have entered very late and with which they are today playing catch-up. Long before Australian offline retailers started making their products available online, customers had already become accustomed to buying their products from established online retailers based overseas.

In addition, geographic isolation adversely affects the availability and price of goods in Australia.

“Although we face a tyranny of distance, many consumers still shop globally. They know that there are products that they can find in other parts of the world that are perhaps of better quality, more unique and of a wider range. Take Levi's for example. It is a major brand, but in Australia you only see a subset of the Levi’s corporate product offering compared to the range available in the US, Canada, or even Singapore. Prices also tend to be lower overseas,” Professor Cadeaux says.

The online retailing trend has become more competitive in recent years, especially with the arrival of Amazon in Australia. Many Australian retailers therefore had to follow suit to remain relevant on the market – including supermarkets.

Both Woolworths and Coles – which collectively dominate approximately 62 per cent of the market, opens in a new window – have had to change to keep up with customers’ evolving needs. Today, both supermarkets provide home deliveries and ‘click and collect’ options to appeal to the time-poor customer. Just a few days ago, Woolworths was named Top Online Retailer by e-commerce intelligence specialist Power Retai, opens in a new windowl.

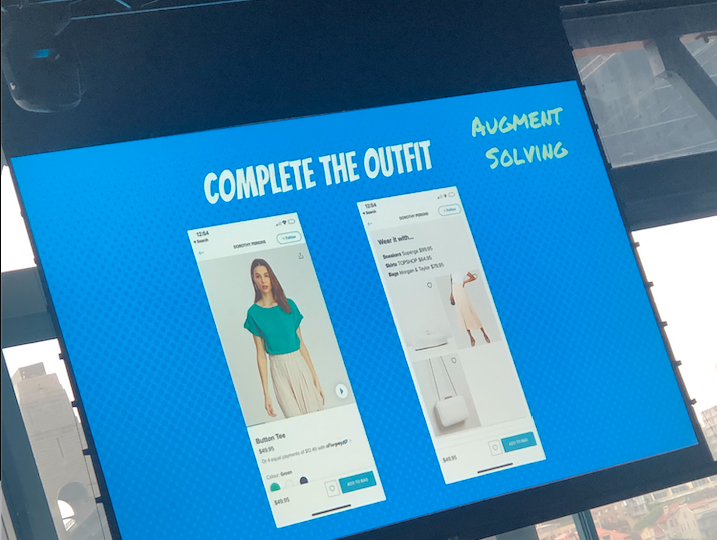

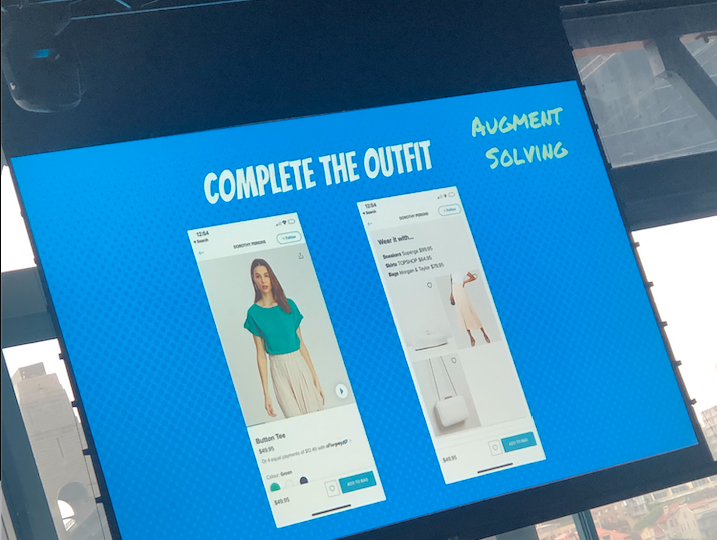

Addressing the main issue of optimising online service and delivery, Kshira Saagar, opens in a new window, Head of Data Science and Analytics at The ICONIC, presented his case study at UNSW’s Marketing Analytics Symposium Conference and shared how the entire model at The ICONIC is made in-house. This in turn has helped The ICONIC deliver a higher level of customer service.

“The ICONIC is a fashion company that does data analytics. We use data to write algorithms to make our customers’ decision-making process easier. An example is how we created an algorithm to help customers complete outfits or search for similar styles on the website just by taking a photo from their phone. Our service is the equivalent of 200,000 human skills sorting through 10 million images. As a result, the average customer’s basket has increased by 30-40 per cent” Mr Saagar said.

Kshira Saagar, Head of Data Science and Analytics at The ICONIC, presenting the 'complete the outfit' function at UNSW Business School's 2020 Marketing Analytics Symposium.

How about brick and mortar stores?

In addition to online retailing challenges, many physical stores have experienced setbacks such as high labour costs and real estate costs in urban centres. As a trade-off to being centrally located, middle tier retailers, restaurants and small establishments have become susceptible to the ups and downs of macroeconomic conditions.

“In many cases, you cannot run a business at a lower volume level – you have to have that consistent, high level of business volume. Even then, it can be hard. Busy restaurants may still not be profitable due to high labour costs and rent.

“Low volume or low margin could be a sustainable model in other parts of the world where labour costs are low. However, it is far more challenging in Australia’s retail climate – especially if you start expanding branches and exposing yourself to more financial risks. The same applies to apparel retailers.”

However, the scenario can be different for retailers in the luxury market, hard discount market or businesses with a unique concept offering.

Do customers prefer value or a bargain?

Another contributor to the retail collapse relates to a misalignment with consumers’ perception of value. People do not necessarily want cheaper products. They want value.

“They want products that will last a long time, they want excellent workmanship or maybe even a particular country of origin,” Professor Cadeaux says.

Value is also not limited to discounts. For example, many people living in densely populated cities like Jakarta, associate value with convenience and as such can now live in a housing complex adjacent to or on top of a mall so they do not have to venture out in dense traffic to do their shopping.

Can loyalty programs help to retain customers?

Professor Cadeaux observes that loyalty programs only work to a certain extent – mainly due to customers’ over-reliance on discounts. Savvy customers have educated themselves on the retail climate and have learned when to expect markdowns. This is particularly pervasive in middle-tier markets.

“It is particularly unfavourable for retailers because I do not think they ever expect to sell most of their products at full price. Customers today are not making a full price purchase unless it is fast fashion that will not be replenished. People instead tend to buy for the entire season and stock up during the sales period.

“The risk is that such customers do not have any particular reason to shop at middle tier stores. The brand has almost no value to them as they only buy what is on sale and do so across brands,” he says.

What should retailers focus on to avoid another retail collapse?

Today, many retailers offer almost identical products, thereby giving customers the choice to shop at any store stocking the same product. This raises the question – are customers loyal to the brand or the retailer?

“Fashion retailers have to be better at sourcing and merchandising to remain competitive,” Professor Cadeaux says.

“They cannot afford to be complacent, hoping that they are going to win customers through promotions and cool branding. They need to use real merchandise buyers who can go out in the fashion industry and buy directly and creatively.”

Quality consistency is also key.

Many times, retailers will attract customers with a high-quality product when they first enter the market, but then gradually reduce quality over time to build margins. Price points stay the same, but quality has been traded down. Returning customers are disappointed and don’t come back again.

“This goes against the traditional textbook theory of retail where you bring in entry level customers and incrementally trade them up to higher quality and price points as their income goes up.”

“Many retailers focus too much on their margins and cut costs on product lines. Promotions have increased from 25 per cent of the full price to 75 per cent. Nobody is encouraged to pay full price, and this is not a sustainable model for any business,” Professor Cadeaux says.

Retailers should instead zero in on what matters. More often than not, retailers spend too much on peripherals rather than the core offering of their products.

“Contrary to what many retailers think, consumers do not value store atmospherics – such as the signature scent of a store or specific in-store colour schemes – more than the product itself. No colour can stimulate customer involvement more than the product offering itself. In a supermarket context, people want to see products on the shelf that are fresh, of good quality and good value.”

Rather than relying on store atmospherics to generate more purchases, retailers need to go back to basics, for example, manage inventories more efficiently to keep costs down.

However, Professor Cadeaux says that there are still opportunities for more players to join the market.

“There probably is room, but retailers have to be more creative and maybe use multi-channel models to be a quicker mover in terms of technology.

“Retailers need to differentiate themselves in their service delivery and sustain the quality of their products. They need to be consistent to ensure longer term value for the customer and not expand excessively.”

Professor Jack Cadeaux, Head of School of Marketing, UNSW Business School

The UNSW Business School launched its two-day Marketing Analytics Symposium on 3 February 2020, bringing together business leaders, analysts and practice-orientated marketing scholars from around the world to discuss cutting edge research in marketing analytics.