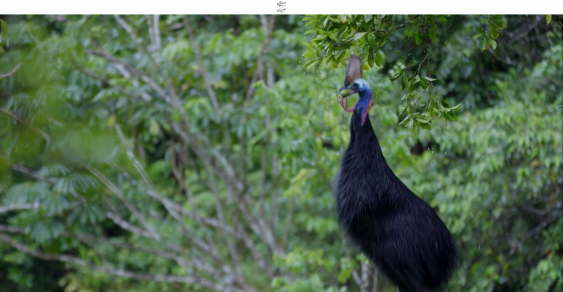

Cassowary leaping high caught on film

By hiding in camouflaged tents for months in the dense rainforest, UNSW PhD student and film-maker Dan Hunter has captured fascinating footage of Australia’s “dino-bird” – the elusive flightless cassowary.

By hiding in camouflaged tents for months in the dense rainforest, UNSW PhD student and film-maker Dan Hunter has captured fascinating footage of Australia’s “dino-bird” – the elusive flightless cassowary.

By hiding in camouflaged tents for months in the dense rainforest, UNSW PhD student and film-maker Dan Hunter has captured fascinating footage of Australia’s “dino-bird” – the elusive flightless cassowary.

Hunter’s latest documentary on the Southern Cassowaries of North-East Queensland reveals insights into the behaviour of these large birds, including their extraordinary feeding behaviour of leaping to great heights to pluck fruit from trees.

Called Dino Bird, the film is currently being broadcast on international wildlife channel Nat Geo Wild, after being selected by National Geographic as part of its 2018 Year of the Bird Campaign dedicated to highlighting bird conservation efforts around the globe.

To make the documentary, Hunter and his colleague Ed Saltau spent nine months filming in a patch of the Daintree rainforest called Cooper Creek Wilderness – part of a world-heritage listed area considered to be the oldest surviving rainforest in the world.

Image: The Natural History Unit

“Cassowaries have to be, hands down, the hardest animal Ed and I have ever filmed before,” says Hunter, who is a PhD candidate in the UNSW School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences.

Adult Southern Cassowaries can grow to up to 2 metres tall and weigh up to 76 kilograms, and the documentary features a large female called Bertha who is thought to be about 60 years old.

The clawed foot of a cassowary. Image: The Natural History Unit

The birds’ most distinctive features are the helmet-like structure on their heads called casques that continue to grow throughout their lifespan. Cassowaries have black plumage with vibrant blue skin around the neck and head, red wattles, as well as large blade-like claws on their feet

To capture the cassowaries on camera, Hunter and Saltau filmed from ‘hides’ - specialised tents that allow the filmmaker to blend in with the surrounding environment.

Although cassowaries are extremely territorial, they do not follow a routine pattern of behaviour. Hunter says they had to get into the minds of the cassowaries, scouting locations where the birds were most likely to be most active, such as water crossings or near fruiting trees.

Bertha is estimated to be 60 years old and is unmistakable with a giant casque that curved slightly to the right. Image: The Natural History Unit

The undisputed matriarch of the rainforest was Bertha, whose age and dominance were on display with her giant casque that curved slightly to the right. That distinctive feature made Bertha unmistakable among the cassowary population.

“Bertha is one of a kind. She just rules the roost,” says Hunter, who witnessed Bertha patrolling through territories during breeding season, making sure the males were doing their job correctly.

Female cassowaries are more dominant than males. During breeding season, female cassowaries invite males into their territory to mate. The female cassowary will then lay the eggs in their mate’s territory, where the male will be responsible for incubating the eggs for almost 2 months and rearing the cassowary chicks.

An adult cassowary and cassowary chick. Image: The Natural History Unit

However, Hunter also saw first-hand the threats to the cassowary population. New property development and clearing of rainforests has meant an increasing fragmentation of the rainforest habitat, disrupting cassowary territories.

“The situation is pretty grim,” he says. “The Daintree world heritage area is locked up – but it doesn’t stop pig populations growing or illegal pig hunting happening. They are some of the biggest threats to cassowaries right now.”

Feral pigs not only eat cassowary eggs; they will also not hesitate to eat cassowary chicks. Illegal pig hunting in the rainforest also has devastating consequences. Whenever pig hunters enter the rainforest, they are accompanied by pig-hunting dogs that create swathes of indiscriminate destruction.

A cassowary chick and adult cassowary. Image: The Natural History Unit

“The dogs are so jacked up with adrenaline that they will kill anything they see,” says Hunter. “A cassowary or a cassowary chick isn’t a match for a pack of four or five pig-hunting dogs.”

Hunter’s passion for wildlife film-making strengthened while he was studying and filming dingoes in the Blue Mountains for his doctorate.

“Australia is just full of incredible wildlife, wildlife stories and conservation stories,” he says.

A kingfisher at Cooper Creek Wilderness Image: The Natural History Unit

In 2016, he and Saltau founded a wildlife filming company called The Natural History Unit, based in Victoria, Australia. The Natural History Unit is currently working with the BBC on the broadcaster’s next landmark natural history series, which is coming out in 2019.

“The BBC is the gold standard when it comes to wildlife film-making, so we are really excited,” says Hunter.

‘Dino Bird’ can be viewed on the Nat Geo Wild Channel or Qantas inflight entertainment.