FactCheck: do bank profits belong to everyday Australians?

In a national advertising campaign, the Australian Bankers’ Association claims banks belong to all of us. But is that true? Mark Humphrey-Jenner investigates.

In a national advertising campaign, the Australian Bankers’ Association claims banks belong to all of us. But is that true? Mark Humphrey-Jenner investigates.

[scald=12757:sdl_editor_representation]

Following mounting pressure from Labor and some National Party MPs, the Turnbull government in December established a Royal Commission into misconduct in the banking, superannuation and financial services industry. Public hearings are now underway.

At the same time, the Australian Bankers’ Association (ABA) has been running a national advertising campaign in which bank branch staff talk about who benefits from bank profits.

The advertisements – broadcast on national television, published in newspapers, shared on social media and displayed on ATMs – state that “nearly 80% of all bank profits go straight back to shareholders and the majority of those shareholders are everyday Australians who own bank shares through their super funds”.

The ABA says bank profits “don’t belong to the banks, they belong to everyday Australians like you”.

Is that right?

The Conversation contacted the Australian Bankers’ Association requesting sources and comment, but did not receive a response.

On the “Australian Banks Belong To You” campaign website, the association cites these references:

The “nearly 80%” figure refers to the dividend payout ratio of the 8 key Australian retail banks averaged over 2016 and 2017. The data are sourced from bank annual reports. The dividend payout ratio is calculated as the sum of the dividends paid divided by the sum of cash earnings.

According to the ATO more than 14.8 million Australians have at least one superannuation fund account (around 40% have more than one). It’s safe to say that many super funds invest in Australian bank shares as part of their portfolio.

This means that millions of Australians own bank shares.

The Australian Bankers’ Association claimed that “nearly 80% of all Australian bank profits go straight back to shareholders”. While we can’t say whether that’s correct for all Australian banks, the statement is broadly correct for Australia’s eight largest retail ABA member banks over the last five years.

The association’s claim that “the majority of those shareholders are everyday Australians who own bank shares through their super funds” is reasonable.

But if you read those statements together as meaning 80% of profits go to Australian shareholders, that would be incorrect. That’s because a proportion of dividend payouts go to non-resident shareholders.

For example, if a dividend was paid on 31 December 2017 by Australia’s ‘Big Four’ banks, non-resident investors would have received between 21.21% and 26.5% of any dividends declared – meaning Australian investors would have received closer to 60% of profits.

The Australian Bankers’ Association (ABA) is an advocacy group representing the interests of the Australian banking industry. The ABA has 24 member banks, but the claim about what percentage of profits are paid to shareholders doesn’t cover all of its 24 members.

On the “Australian Banks Belong To You” campaign website, the ABA said it based its “nearly 80%” claim on “the dividend payout ratio of the eight key Australian retail banks averaged over 2016 and 2017”, with the numbers sourced from bank annual reports.

Dividends are cash payments that listed companies make to their shareholders. The cash payments are often made regularly. The “dividend payout ratio” is the sum of the dividends paid to shareholders in a year, divided by the sum of the cash earnings the company made.

In other words, the dividend payout ratio is the portion of corporate profits that are paid directly back to shareholders. Companies retain the rest of profits, usually to finance future growth.

While the ABA didn’t name the banks it based its claim on, the eight largest retail banks in the ABA are the Commonwealth Bank, National Australia Bank, ANZ, Westpac, Bank of Queensland, Bendigo Bank, Suncorp and Macquarie Bank.

If we look at dividend payout ratios for those eight banks since 2013, we can see that the overall average payout has consistently hovered around 80% for the past five years.

The same is true of the average payout of the ‘Big Four’ Australian banks – Commonwealth Bank, Westpac, ANZ and National Australia Bank.

In 2012, an outlying dividend payout caused the average dividend payout to appear abnormally high. In the preceding five-year period from 2007 to 2011 payout ratios were lower, as you can see in the chart below.

The ABA claimed that of those bank profit distributions, the “majority” go to Australians, including “millions of everyday Australians who own bank shares through their super funds”.

The ABA did not define what it meant by “everyday Australians”. In justifying its claim, the ABA correctly cited Australian Tax Office data that shows that as of June 30, 2016, more than 14.8 million Australians had at least one superannuation fund account.

On its website, the ABA stated it’s “safe to say that many super funds invest in Australian bank shares as part of their portfolio”.

Superannuation funds do typically hold a balanced portfolio that represents the major members of the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX). A typical superannuation portfolio might invest in bonds, and in a portfolio of the largest 200 stocks on the ASX, which would include the major banks. This can be subject to individuals’ investment preferences.

For example, say the fund invests in the largest 200 companies on the ASX, and invests in proportion to the companies’ size (that is – the largest companies get the largest investment). Then, the big four banks would be four of the five largest investments.

Obviously, not all superannuation accounts invest in bank stocks, and portfolios can be structured in different ways. For example, some superannuation funds allow their members to invest only in bonds, and people with self managed superannuation funds choose their own investments.

Some wealthy shareholders, and overseas shareholders, also benefit from holding Australian bank shares. As with all companies, shareholders benefit in proportion to their shareholding. Listed banks have no say over whether wealthy Australians, or overseas buyers, purchase their shares.

But it is fair to say that “millions of everyday Australians who own bank shares through their super funds” benefit from dividend payouts. – Mark Humpherey-Jenner

The Australian Banking Association claimed that nearly 80% of all Australian bank profits go back to shareholders, and that the majority of those shareholders are everyday Australians who own bank shares through their super funds.

Those claims are valid when read independently, as set out above. But they should not be read together as indicating that nearly 80% of profits go to Australian shareholders.

The proportion of dividends that go back to Australians, either directly or through their investment portfolios, would be less than 80% of bank profits.

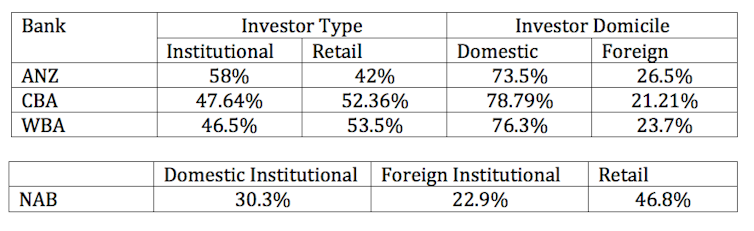

Reviewing the investor profiles of ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac shows that on December 31, 2017, Australian investment ranged from 73.5% to 78.79% across the big four banks, and institutional investment, which includes superannuation funds and other financial institutions, represented slightly under half of investors.

The high representation of domestic institutional holdings demonstrates the significance of bank shares in most investment portfolios, including superannuation funds.

So if a dividend had been paid on 31 December 2017 for Australia’s ‘Big Four’ banks, non-resident investors would have received between 21.21% and 26.5% of that dividend declared, meaning Australian investors would have received closer to 60% of profits. – Helen Hodgson

The Conversation’s FactCheck unit is the first fact-checking team in Australia and one of the first worldwide to be accredited by the International Fact-Checking Network, an alliance of fact-checkers hosted at the Poynter Institute in the US. Read more here.

![]() Have you seen a “fact” worth checking? The Conversation’s FactCheck asks academic experts to test claims and see how true they are. We then ask a second academic to review an anonymous copy of the article. You can request a check at checkit@theconversation.edu.au. Please include the statement you would like us to check, the date it was made, and a link if possible.

Have you seen a “fact” worth checking? The Conversation’s FactCheck asks academic experts to test claims and see how true they are. We then ask a second academic to review an anonymous copy of the article. You can request a check at checkit@theconversation.edu.au. Please include the statement you would like us to check, the date it was made, and a link if possible.

Mark Humphery-Jenner is an associate professor of finance at UNSW Sydney.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.