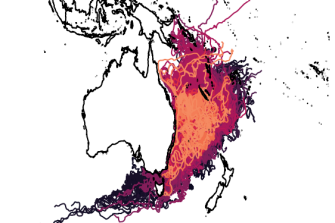

Bourg N, Schaeffer A, Cetina-Heredia P, Lawes JC, Lee D (2022) Driving the blue fleet: Temporal variability and drivers behind bluebottle (Physalia physalis) beachings off Sydney, Australia. PLOS ONE 17(3): e0265593. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265593

Bourg N, Schaeffer A, Molcard A, Luneau C, Hewitt DE, Chemin R. Ocean wanderers: A lab-based investigation into the effect of wind and morphology on the drift of Physalia spp. Mar Pollut Bull. 2024 Oct;207:116856. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116856

Bourg, N., Schaeffer, A., & Molcard, A. (2024). East Australian Current system: Frontal barrier and fine-scale control of chlorophyll-a distribution. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 129, e2023JC020312. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JC020312

Global genomics of the man-o’-war (Physalia) reveals biodiversity at the ocean surface. Samuel H. Church, River B. Abedon, Namrata Ahuja, Colin J. Anthony, Diego A. Ramirez, Lourdes M. Rojas, Maria E. Albinsson, Itziar Álvarez Trasobares, Reza E. Bergemann, Ozren Bogdanovic, David R. Burdick, Tauana J. Cunha, Alejandro Damian-Serrano, Guillermo D’Elía, Kirstin B. Dion, Thomas K. Doyle, João M. Gonçalves, Alvaro Gonzalez Rajal, Steven H. D. Haddock, Rebecca R. Helm, Diane Le Gouvello, Zachary R. Lewis, Bruno I. M. M. Magalhães, Maciej K. Mańko, Alex de Mendoza, Carlos J. Moura, Ronel Nel, Jessica N. Perelman, Laura Prieto, Catriona Munro, Kohei Oguchi, Kylie A. Pitt, Amandine Schaeffer, Andrea L. Schmidt, Javier Sellanes, Nerida G. Wilson, Gaku Yamamoto, Eric A. Lazo-Wasem, Chris Simon, Mary Beth Decker, Jenn M. Coughlan, Casey W. Dunn; bioRxiv 2024.07.10.602499; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.10.602499

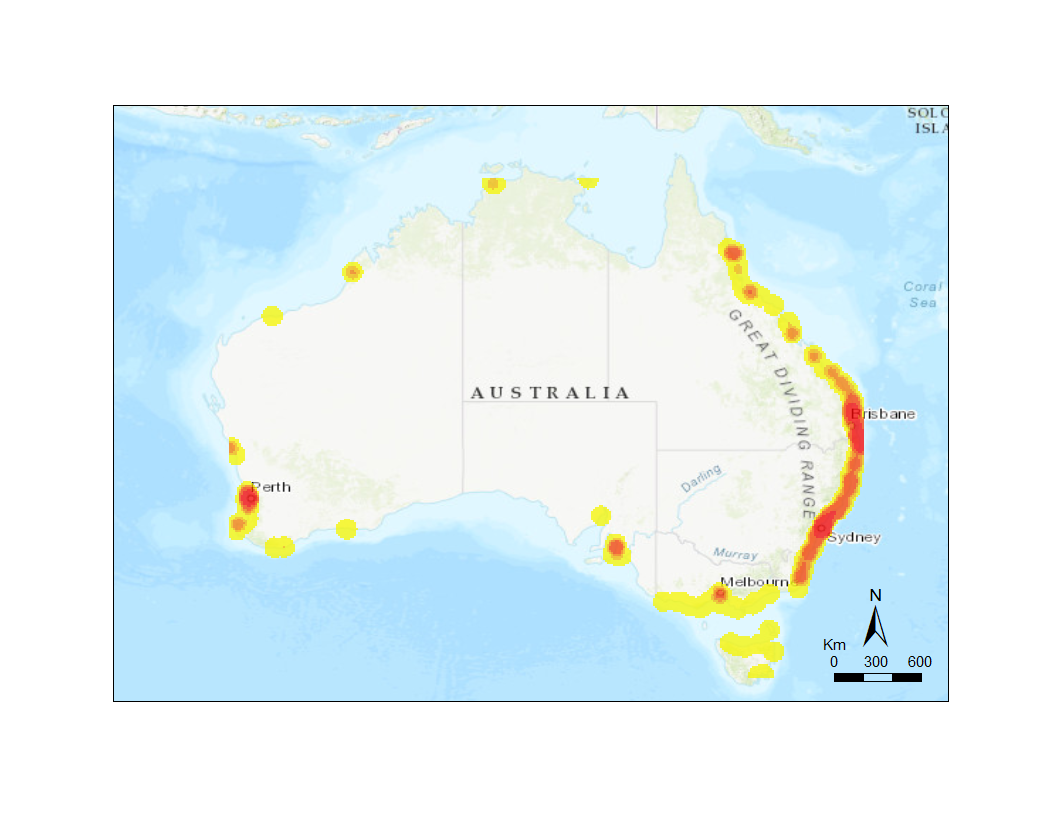

Lee, D., Schaeffer, A., and Groeskamp, S.: Drifting dynamics of the bluebottle (Physalia physalis), Ocean Sci., 17, 1341–1351, https://doi.org/10.5194/os-17-1341-2021, 2021.

https://os.copernicus.org/articles/17/1341/2021/os-17-1341-2021-corrigendum.pdf

Other references

Munro, C., Vue, Z., Behringer, R., and Dunn, C.: Morphology and development of the Portuguese man of war, Physalia physalis, Sci. Rep.-UK, 9, 15522, https://doi.org/10.1101/645465, 2019

.jpg)