Platypuses in the Park

The quest to bring one of Australia's most beloved animals back to Royal National Park

On the banks of a Snowy Mountains river in the early hours of the morning, two scientists huddle round a fire in near-freezing temperatures.

Platypus experts from UNSW Sydney, Dr Gilad Bino and Dr Tahneal Hawke, are on a mission to select 10 of the animals from the wild – six females and four males – to be the founding members of a new population of platypuses in Royal National Park. The platypus has not been seen there for more than half a century, prompting experts to conclude it has been locally extinct for decades.

Setting up camp in challenging locations is par for the course for platypus experts. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Setting up camp in challenging locations is par for the course for platypus experts. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Gilad and Tahneal are no strangers to these rugged conditions, having long been involved with conservation programs to protect platypuses against the confounding threats of climate change, vanishing habitats due to human development and disconnected waterways.

But they're part of a larger, equally dedicated team of partner organisations that have joined forces to restore this iconic animal to its rightful place in Royal National Park.

UNSW Sydney, led by Director of the Centre for Ecosystem Science Professor Richard Kingsford, has a strong track record in rewilding projects and restoration of Australia's threatened native fauna.

After engaging with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Services to ensure the project was a good fit with the park's environmental and conservation goals, the UNSW team partnered with two other organisations with a long history in animal welfare.

Taronga Conservation Society – a not-for-profit organisation affiliated with Sydney and Dubbo's famous zoos – would play a vital role in looking after the welfare of the platypuses selected to be the founding members of a new Royal National Park population.

And WWF-Australia, whose raison d'être is to prevent vast numbers of wild, unique Australian animals from being pushed to the edges of existence, was instrumental in funding this project.

For the UNSW conservation scientists, the platypus project follows three years of careful planning that was almost derailed by the severe flooding events of 2022. But such is their passion to protect this unique animal, not even dangerous weather could dampen their enthusiasm to see the project through. Being wet, uncomfortable and sleep-deprived is all par for the course when you've got one of the best jobs in the world.

UNSW's conservation scientists

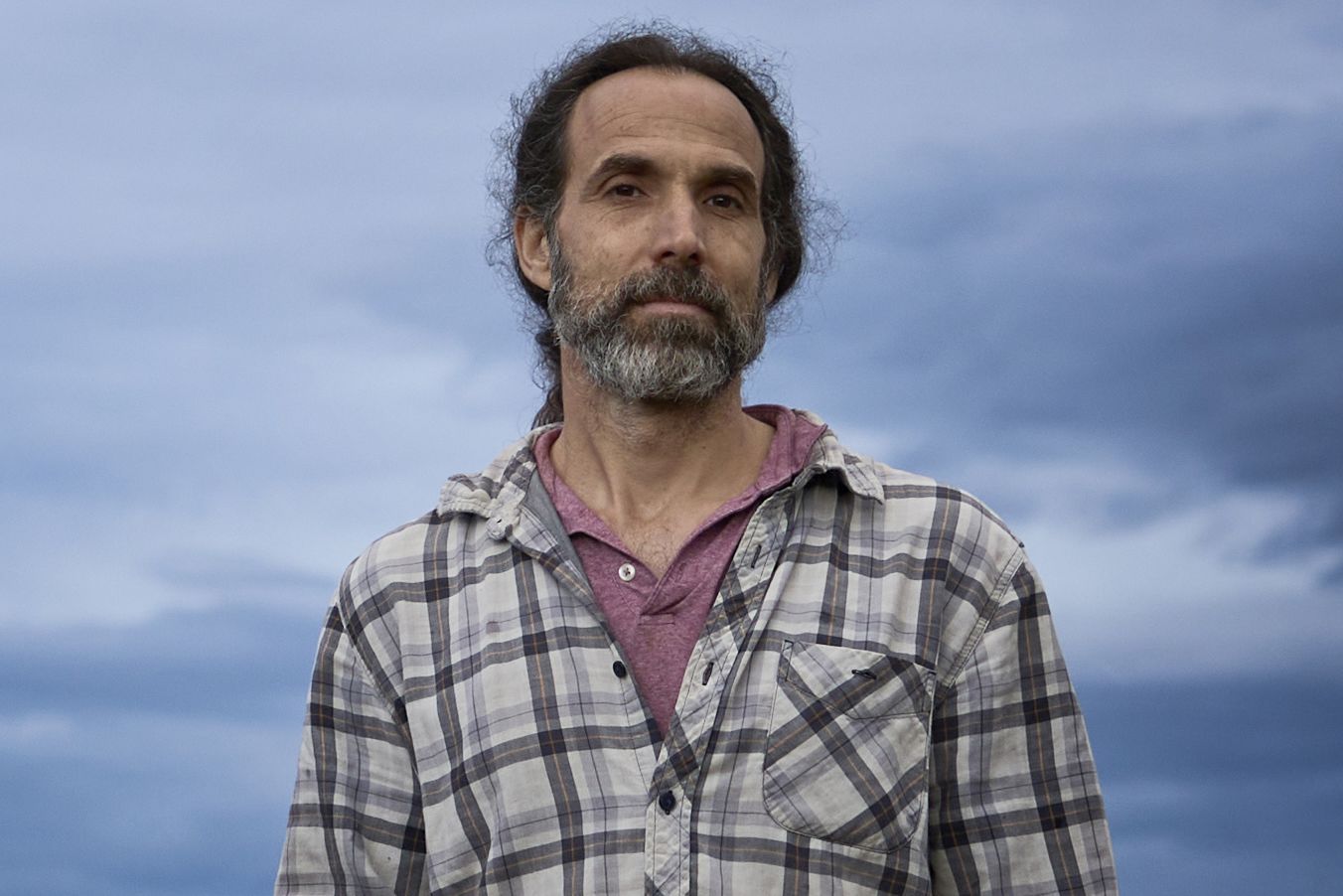

Dr Gilad Bino

Senior Lecturer, Centre for Ecosystem Science, UNSW Sydney

Dr Bino has two decades of ecological research and conservation under his belt. He has been researching platypuses for more than seven years, which involves assessing populations, demographics, health, and behaviour. Dr Bino has already been involved in a translocation of sorts. In 2019 he helped move platypuses from Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve to Taronga Zoo due to drying pools resulting from the 2019 droughts. The platypuses were returned to their Tidbinbilla home following rains in 2020.

Dr Tahneal Hawke

Postdoctoral researcher, Centre for Ecosystem Science, UNSW Sydney

Dr Hawke has been a proactive participant in the conservation of native Australian animals since her undergraduate years. She volunteered on projects to protect native animals such as flatback turtles, bilbies and mountain pygmy possums. She now has seven years’ experience trapping and handling platypuses, including assessing population sizes, demographics, health, and tracking movements. She led the trapping for the translocation of platypuses from Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve to Taronga Zoo in 2019.

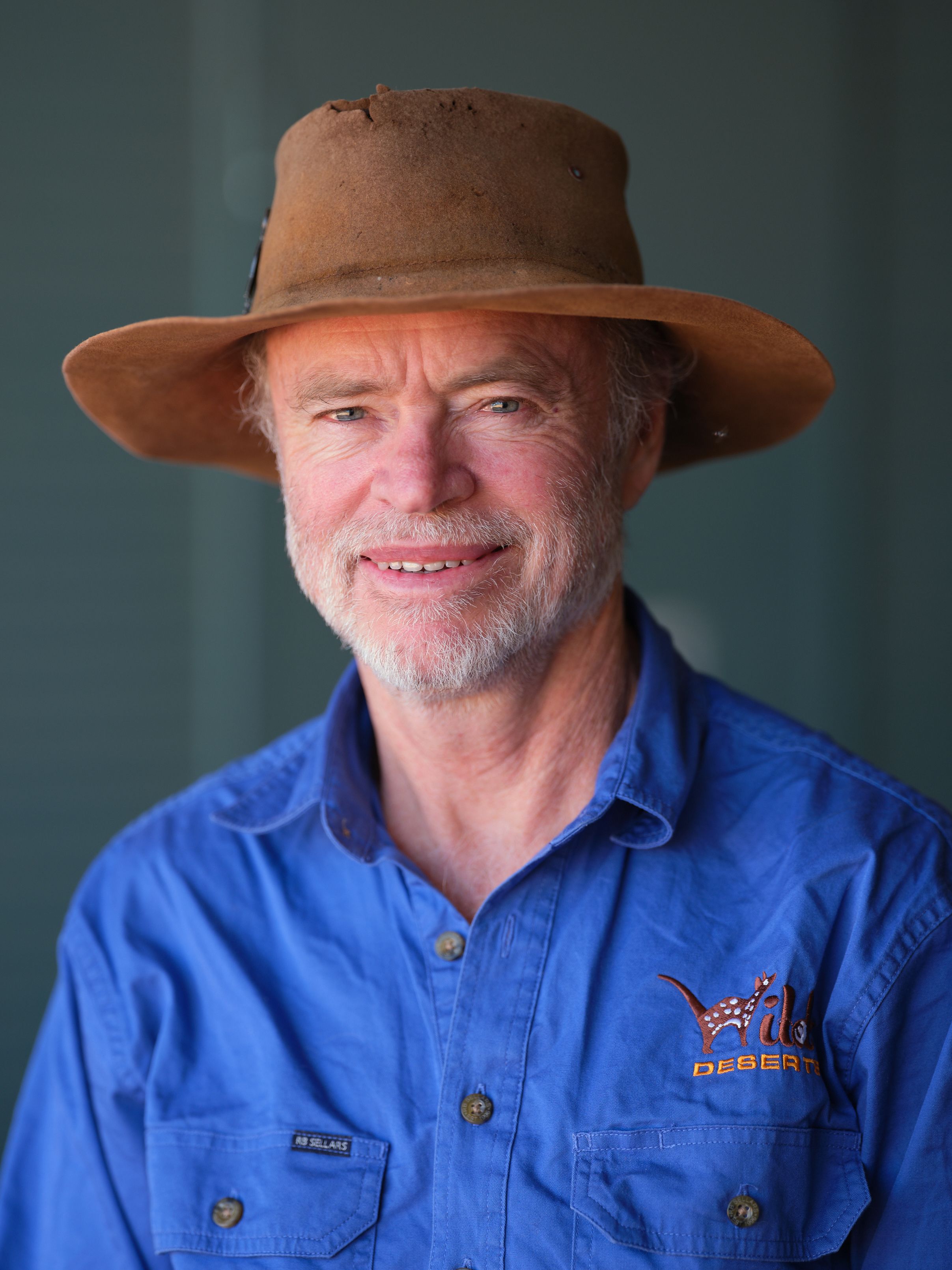

Prof. Richard Kingsford

Director of the Centre for Ecosystem Science, UNSW Sydney

Professor Kingsford has made a lifetime contribution to the research of aquatic ecosystems and wetlands. He is perhaps best known as project leader of Wild Deserts, reintroducing seven locally extinct mammals to Sturt National Park. More recently he has overseen the planning and preparation of the project to reintroduce platypuses to the Royal National Park, and while not in the field as regularly as Dr Bino and Dr Hawke, has put in some solid hours in the wild where his expertise on river ecology has been invaluable.

How do you pick a platypus?

After three years of careful planning, Gilad and Tahneal set out on an exhausting tour of seven river sites in southern NSW between the Kangaroo Valley and the Snowy Mountains.

The duo's objective was to gather no more than two platypuses from each river site to limit the impact on existing population numbers – some of which had more than a dozen per kilometre. This followed years of surveying platypus populations throughout NSW.

Because platypuses are nocturnal animals, all work had to take place between dusk and dawn.

On one particular night, the team caught seven platypuses. Gilad says whether or not the platypuses caught in the nets ended up in the final 10 for Royal National Park, it was a great opportunity to collect data about each river population.

This stretch of river in the Snowy Mountains was one of seven sites the UNSW team visited to collect some of the 10 platypuses for translocation to Royal National Park.

Platypuses were caught using unweighted gill nets and fyke nets like this one.

After setting the nets, Tahneal and Gilad made some final preparations before a long night at the office...

...which is when the real work began. On some evenings, the pair were finished by midnight, while on others, they worked until first light, grabbing naps where they could.

In the quiet of the night, the duo rowed out to investigate the nets after hearing the distinctive splashing of platypuses from the river bank.

The pair untangled a plucky adult female. Because it's so difficult to age platypuses once they're past the age of two, other criteria for selection were used such as size, absence of scars or injuries, a nice sheen on their coats and plenty of fat reserves.

Meet Delphi, the first female collected from southern NSW rivers who is one of the founding members of the new population of platypuses in Royal National Park.

In the back of a truck, Gilad made measurements and checked Delphi's vital signs and overall health.

Dr Phoebe Meagher from Taronga Conservation Society and Tahneal carefully loaded Delphi into a hutch before spiriting her away to Taronga Park Zoo, Sydney, a few hours' drive away.

Tahneal and Gilad set an unweighted gill net that will temporarily trap platypus. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Tahneal and Gilad set an unweighted gill net that will temporarily trap platypus. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

A platypus dives back into the river after being released by the scientists. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

A platypus dives back into the river after being released by the scientists. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Tahneal checks the river for any visible platypus activity. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Tahneal checks the river for any visible platypus activity. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

The Milky Way glows more brightly when viewed from the countryside. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

The Milky Way glows more brightly when viewed from the countryside. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Tahneal rests next to the campfire between platypus captures. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Tahneal rests next to the campfire between platypus captures. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

A platypus is loaded into an SUV bound for Taronga Zoo, Sydney. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

A platypus is loaded into an SUV bound for Taronga Zoo, Sydney. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

A platypus's bill is quite soft and is covered with thousands of receptors that help the platypus detect prey. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

A platypus's bill is quite soft and is covered with thousands of receptors that help the platypus detect prey. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Male platypuses have a spur on the inner side of each ankle that is connected to venom glands. The venom is potent enough to kill small animals and cause intense pain in humans. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Male platypuses have a spur on the inner side of each ankle that is connected to venom glands. The venom is potent enough to kill small animals and cause intense pain in humans. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Platypuses don’t have teeth inside their bills but instead use keratinous pads to grind their food. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Platypuses don’t have teeth inside their bills but instead use keratinous pads to grind their food. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Gone, but not forgotten

Royal National Park is one of the oldest national parks in the world, established in 1879 by the colonial government of New South Wales.

But prior to European invasion in 1788, it was part of the Dharawal nation. The Dharawal people's traditional lands run down the coast south of what is now Sydney, stretching from today's La Perouse down to Bombadery.

The platypus, or Djumulung in the Yuin language of the South Coast, has always been an important feature of Country and culture. They were occasionally spotted in the rivers flowing through Royal National Park until the beginning of the 1970s.

But in the past 50 years, confirmed sightings of platypuses have dwindled to nothing, although there has been some debate about unconfirmed sightings at the turn of the millennium.

For example, in 2000 a couple of canoeists reported a possible platypus sighting in Royal National Park. One thought it was a platypus, but the other wasn't so sure and thought it could have been a fish.

Whether it was 20 years, 30 years or 50 years ago that platypuses last swam through the Hacking River in Royal National Park, experts thought the platypus was locally extinct in the river, and has been likely absent for decades.

To test this hypothesis, a team of UNSW scientists and volunteers from Friends of the Royal conducted environmental DNA surveys at the Park in 2021. They sampled the water and looked for evidence of the animals that frequented the river.

These eDNA surveys found traces of as many as 250 land and water species in the park’s Hacking River and Kangaroo Creek.

But no sign of any platypus.

What happened to them?

It's likely there was not one single cause, but rather a combination of factors that led to the disappearance of the platypus from Royal National Park.

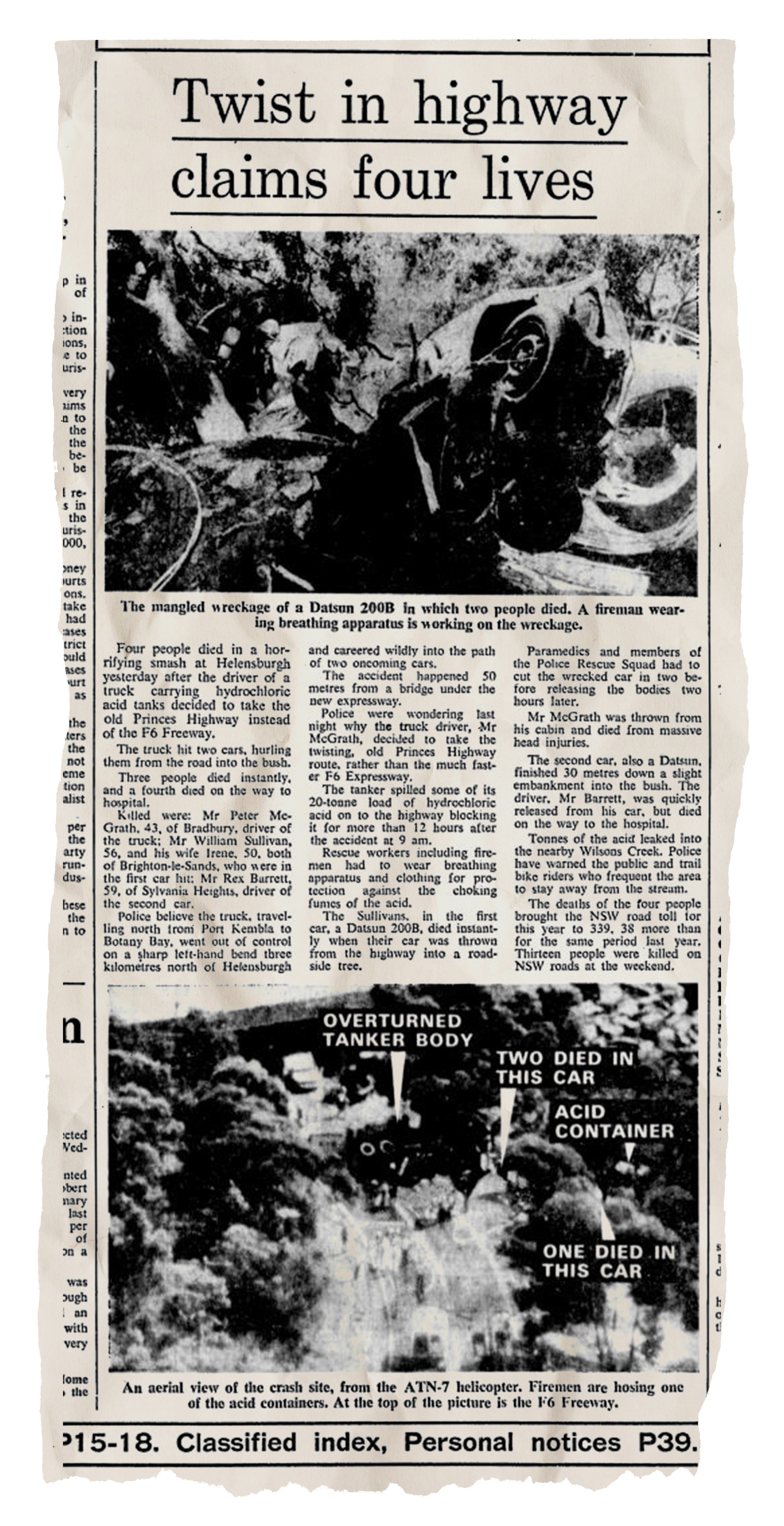

A popular theory was that a chemical spill from a fatal crash on the nearby Princes Highway in 1981 washed into the rivers and hastened the demise of the platypus in the Park, already impacted by fragmentation and polluted waterways.

Source: The Sydney Morning Herald, April 13, 1981

Source: The Sydney Morning Herald, April 13, 1981

Another contributing factor may have been the effect of feral animals in the Park. Red foxes and feral cats are known to prey on platypuses especially during drought years when rivers run dry and platypuses are exposed as they travel overland in search of more water. A recently implemented baiting program will help control fox numbers.

Deer are also feral animals in the National Park. Their trampling of foliage creates soil instability on the banks of the river, making it harder for platypuses to make burrows for nesting.

Gilad says it's difficult to pinpoint one overwhelming reason for the platypuses' disappearance but the group believes the platypuses stand a good chance of survival this time around.

"Siltation of the park’s rivers as a result of upstream development, poor operation by the coal mine, loss of connectivity and invasive species may have all contributed," he says.

"Those potential causes relating to industrial development may have abated over the past few decades which could mean the park is in a general upward trajectory. Meanwhile, invasive species are now being managed."

A fox is captured on one of Royal National Park's cameras. Photo: Royal National Park

A fox is captured on one of Royal National Park's cameras. Photo: Royal National Park

Bringing them back home

Reintroducing platypuses to the National Park was not just about trying to right past wrongs caused by human activity, Gilad says, but part of a longer game plan that aimed to strengthen the species' survival into the future.

Bringing platypuses back into Royal National Park will help their long-term survival, Dr Bino says. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Bringing platypuses back into Royal National Park will help their long-term survival, Dr Bino says. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

"The survival of any species depends on the free movement of individuals from one group to another. This is because the need to exchange genetic material is paramount to a species' long-term survival," Gilad says.

"Unfortunately, humans have not protected the environment and we've seen the platypuses' habitat diminish.

"On top of that, we've broken what little connections platypus groups had to each other by damming rivers and making it impossible for that flow of genetic information to continue back and forth along the waterways."

But, as some critics say, maybe there was a good reason why platypuses disappeared from Royal National Park. Some point to the nearby coal mine at Helensburgh as a potential polluter of the nearby rivers that feed into the Hacking. In 2022, floods may have contributed to a polluting event where coal particles washed into the nearby tributaries.

The safety and well-being of the platypuses selected for translocation has always been paramount, Tahneal says. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

The safety and well-being of the platypuses selected for translocation has always been paramount, Tahneal says. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

But following recent testing carried out in early 2023, the water quality in the Hacking was shown to be good and brimming with life for platypuses to feast on – such as small aquatic animals like dragonfly nymphs, caddis fly larvae and small shrimps.

"We would never think of introducing platypus into an unsafe environment," Tahneal says.

"For the past couple of years we have been making sure that all the conditions are right before getting to the business end of this translocation project. And you don't do that without first testing the waters...literally!"

Professor Richard Kingsford says testing revealed water quality and food supplies in the Hacking River were good. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Professor Richard Kingsford says testing revealed water quality and food supplies in the Hacking River were good. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

"We have been careful to keep monitoring water quality and platypus food availability through the extreme floods of last year, the pollution event and now after the flooding this year. It is really encouraging to see the animals that platypuses eat and depend on doing so well and the good water quality."

From the bush to the big smoke

Once selected for translocation to Royal National Park, each platypus was taken by car to Taronga Park Zoo in Sydney's north shore for a short stay in the zoo's purpose-built facilities.

These consisted of six 5000L water tanks and 12 rest-boxes that the platypuses could temporarily stay in for the next few days.

The facilities were large enough to ensure that as each platypus arrived, they could be quarantined while Taronga's expert staff assessed their health and physical condition.

Here, a female platypus named Kombucha explores a water tank of her temporary home at Taronga.

P-Day arrives

On a cool, mid-autumnal afternoon, just an hour or so before dusk, the big moment arrived to release the first of the platypuses into Royal National Park from the banks of the Hacking River.

The plan: releasing six females, with the remaining four males to be released a week later.

Representatives from UNSW, the NSW State Government, National Parks & Wildlife, Taronga Zoo and WWF-Australia were there to witness the return of the Royal National Park's native apex predator.

But first, the contingent was welcomed to Dharawal country by Indigenous leader and Park Ranger, Uncle Dean Kelly.

He told the Dreamtime story about how Djumalung, or the platypus, came to be.

Wailwan man Uncle Dean Kelly from NSW Parks & Wildlife delivered a Welcome to Country that invoked the Dreamtime spirits to prepare the river for the return of the platypus. Listen to the Dreamtime story about Djumulung below (1m 24).

How Djumulung, or the platypus, came to be in the Dreamtime

NSW State Environment Minister Penny Sharpe was given the honour of releasing the first of the female platypuses – Delphi.

Next to be sent into the water was a female called Pandora, here being released by the UNSW team of Richard Kingsford, Gilad Bino and Tahneal Hawke, with a little help from Uncle Dean's grandson, Waratah.

The Royal family

Released into the Hacking River that day were six female platypuses, each given a unique name.

After Delphi and Pandora came Kombucha, Kryptonite, Daiki and then Gerzgerzitsky.

The following week it was the males' turn. The handlers had to take extra care letting them out of the bags due to their venomous spurs – which by all accounts can cause an injury that is incredibly painful and can take months to heal.

In order of release, the males were: Draco, Norris, Prometheus and a particularly mischievous platypus called Chaos. Instead of heading for the river, Chaos darted left and ran straight under the legs of onlookers.

Just the beginning

All 10 platypuses were tagged with a small tracking device that allows the scientists and National Park rangers to monitor their activity and movements.

Gilad points a radio antenna toward the river to pick up signals from the 10 platypuses released a month earlier. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Gilad points a radio antenna toward the river to pick up signals from the 10 platypuses released a month earlier. Photo: UNSW Sydney/Richard Freeman

Data has shown that since being released into Royal National Park, the platypuses have explored the river and some have even made burrows in the river banks – which is a healthy sign and bodes well for breeding.

Platypuses tend to be territorial and inhabit 1 to 2km stretches of river on average, with males closer to 2km and females closer to 1km. They have been recorded traveling dozens of kilometres, perhaps in search of a new home or to avoid degrading conditions.

Gilad and Tahneal plan to return to the river next year to check on the condition of each platypus and the exciting prospect of whether any juveniles – or 'puggles' – have hatched.

About half of females in a population breed in a given year which can be influenced by the prevailing conditions, so the scientists are cautiously optimistic about seeing the population grow over the next few years.

If this translocation is a success, they plan to do a similar translocation down the track. This would give the founding population of platypuses enough genetic diversity and the best chance to thrive into the future at Royal National Park.

Credits

Story: Lachlan Gilbert

Photos: Richard Freeman

Video: Jake Willis, Marty Jamieson, Lee Henderson, Harrison Vincent

Multimedia production: Lachlan Gilbert, Brad Hall, Richard Freeman, Marty Jamieson, Jake Willis, Aleksandr Wynne, Ian Joson, Isabelle Dubach

Social media: Mitch Lamm, Oliver Watt

Media enquiries

Please contact Lachlan Gilbert, News & Content Co-ordinator, by phone on + 61 2 9065 5241 or email at lachlan.gilbert@unsw.edu.au