Had your data leaked in 2022? Blockchain could have the answer

We saw enormous amounts of data leaked in 2022. UNSW Business School's Dr Eric Lim asks if blockchain offers a way to stop it happening again.

We saw enormous amounts of data leaked in 2022. UNSW Business School's Dr Eric Lim asks if blockchain offers a way to stop it happening again.

Kate Bettes

UNSW Business School

+61407701034

k.bettes@unsw.edu.au

The famous quote 'Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result' is often, falsely, attributed to Einstein. But when it comes to the cybersecurity industry, and their attempts to prevent hackers, it seems an apt phrase, whether or not the world’s most famous scientist actually said it.

Why do I say this? Because the cybersecurity industry incessantly and continually insists on more training and awareness education every time massive data breaches happen.

Let’s go back a step for a quick reminder of where we’re at in Australia when it comes to cyber breaches, as of early 2023. Uber was breached in September 2022 when 77,000 Uber employee details were leaked, followed by Optus not long after, with over 9.8 million (or 10 per cent of their customers) customer details stolen in a cybercriminal hack.

Then it was Medibank, with approximately 9.7 million current and former customers and associated representatives having their personal details stolen by a ransomware group, and Woolworth’s subsidiary, MyDeal, with 2.2 million customers affected.

All of this has left a portion of those whose data was leaked open to increased risk of spam messages to their social media accounts and phone numbers, dodgy text messages, phishing emails and other phishing attacks that lead to deployment of malicious software (also known as malware), risk of identity theft and more.

With these breaches came the usual call for government to spend more money on cybersecurity programs, “to ensure businesses conduct cybersecurity practices safely and correctly” and “improving education and awareness of cybersecurity is more important than ever, especially for business leaders”.

Did your data get leaked in 2022? Photo: Getty

These breaches have come with calls for more onerous use of two-factor authentications and consistent nagging of organisations to their employees to change their strong passwords and login credentials periodically, all in an attempt to prevent sensitive information being leaked from an individual.

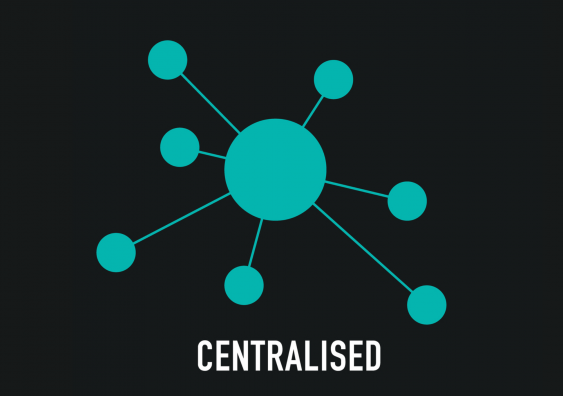

But it is too easy to shift the blame of these breaches to the employees while speaking nothing of the increasing desire of all organisations to hyper centralise the data of their employees and their customers.

But the overwhelming chances are such breaches will again happen down the road within the current cybersecurity paradigm.

In my mind, the major issue is not just education. It is the way that our information is being stored in creating a single point of failure and major security risk.

Having all this information lumped together related to hundreds of thousands, even millions of customers, represents a ginormous honeypot that the malicious bees of cybercrime, seeking information they can sell, are bound to be drawn to.

The centralised model of data storage is common... Photo: Getty

(I mean, haven’t we mocked to death, the Empire in the Star Wars movies, and the Empire’s inability to learn from past mistakes and insisting on creating single points of failure in designing their Death Stars? Not once but twice!?)

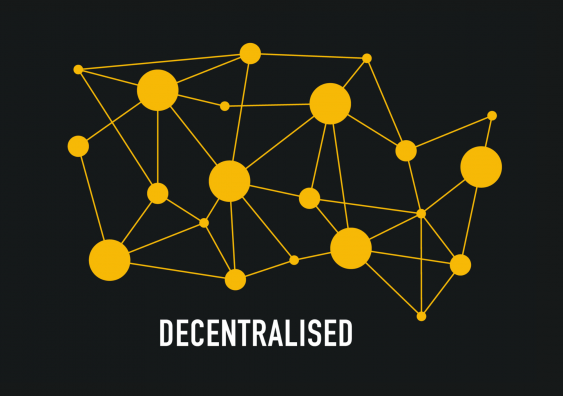

Information being lumped together is a major design failing point that awareness education is going to find difficult to solve. So, what about completely rethinking the design with the help of blockchain-enabled decentralised identities?

What if, instead of centralising the data in an alluring honeypot, we allow each employee and customer of these organisations to hold on to their own data?

... but what about decentralised identity? Photo: Getty

We could skip over this single point of failure by decentralising the data and give each customer and employee sovereignty over their own data points, using blockchain enabled Decentralised Identity (also known as DID).

What is DID? It has a well-defined standard based on the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) as a ‘new type of identifier that enables verifiable, decentralised digital identity … In contrast to typical, federated identifiers, DIDs have been designed so that they may be decoupled from centralised registries, identity providers, and certificate authorities’.

This means instead of a company holding all the customer’s data in an alluring one-stop-info-shop, everyone is tasked with maintaining sovereignty over their own data.

How DID works is not too difficult to understand.

There are three basic components: 1) the individual holder, 2) the issuers of digital credentials, and 3) the verifier. The entire process flows across these three entities and is founded on the utilisation of the public-private key pairs that are very common in cryptography and similar to how cryptocurrencies work.

The individual holder denotes a pointer on the blockchain represented by their public key. This pointer is public and can be broadcasted publicly and globally as representative of the individual holder. The individual holder keeps their private key secret in a local device or in their memory and will never reveal it to anyone.

The individual holder accumulates pieces of information associated with their economic identity known as digital credentials.

Examples of digital credentials could be your driver’s licenses, education certificates, criminal records and passports. They are issued by the relevant authorities (who would have also registered their individual public keys on the blockchain as public pointers that are broadcasted publicly while also keeping their private keys safe).

When a digital credential is issued by the issuer to an individual, they are signed with the digital signatures created by the issuers and the credentials are then stored by the individual.

The final component of the DID is the verifier. These verifiers can take the form of organisations or other individuals with whom the individual holder interacts. The verifiers can request specific information associated with the digital credentials held by the individual holders for transactions to occur or for services to be rendered.

When handing over this information, the individual holder would add their own digital signature to this information to authenticate it.

In short, the verifier will be able to use the two digital signatures (one from the issuer plus the other from the individual holder) associated with the requested piece of information and validate them with the respective public keys publicised on the blockchain by both the issuer and the individual holder.

In the entire process, the digital signatures are specific to the particular instantiation of the information transferred and cannot be replicated by anyone who does not possess the respective private keys, therefore preserving the authority of the individual holder to have sovereignty over their own privacy.

Everything from your birth certificate to your drivers licence could be stored using blockchain enabled Decentralised Identity. Photo: Getty

When we have a decentralised model of data management, we are essentially diffusing vulnerabilities to the edges.

Continuing the metaphor, as opposed to attacking the honeypot and making off with a whole jar, attackers will at most get a drop. A lot less worth the time and effort for reward!

Of course, no system is perfect. Individuals would still be vulnerable to cyberattacks with DID. But, in this scenario, if an individual got careless and is subsequently hacked, it doesn’t affect anyone else who has been careful in protecting their own identity. Instead of storing everyone’s information on a central server, DID allows individuals to hold their own information in their own devices.

So, if an attacker wishes to carry out cybersecurity attacks, they will have to target every mobile device. That’s costly and impractical. Such a concept applies to the protection of any sensitive data such as financial and health data where the individual is the only one who will decide how and with whom they would like to share data with.

One of the major downsides is that the concept of the DID assumes that the individuals can and will be willing to assume responsibility for making sure they keep their devices secure. This means, no leaving their private keys written down, lying around for attackers, and avoid undertaking risky behaviours like accessing keys on a web browser when on public Wi-Fi.

So, if an individual is careless and suffers an attack, it is on them if their financial information and more is leaked.

In this sense, this goes back to a fundamental argument about the nature of human beings and whether they can be trusted to be responsible for themselves.

But I am a strong believer that we need to reflect on our incentive system when it comes to cybersecurity. If the incentive system is wrong, no amount of compulsion or exhortation or education from a higher power will change an individual’s behaviour.

But if individuals are incentivised to protect the data, because it is purely, and tangibly their own, they could be more strongly incentivised to protect it themselves.

Using decentralised identities means individuals - not organisations - would be responsible for protecting their own data. photo: Getty

There are some obstacles towards the establishment of DID. As the concept is very new, there currently does not exist a strategic roadmap towards the realization and establishment of this vision, both at the national and international level.

The first step towards setting up a DID and giving everyone a digital identity is the need to agree on a set of procedures that will allow people to register their DIDs on a blockchain with own their relevant governmental agencies.

This would apply to every individual, so they are recognisably connected to their DID and the connection is made official and auditable on the blockchain. This also applies to all government agencies who would also be officially connected to a unique DID on the blockchain, for auditability.

This systematic creation of an auditable trail of connections between the DIDs and their real-life entities would be the first and most important step, something which would preferably be recorded on an open decentralised blockchain. This will ensure that in the event of political or civil upheaval, that the DIDs would still be auditable by others.

(Think of it like your work email. This email is often publicly available for all to find, but only you can use it. But if the company goes bust overnight, you will lose that email. But the blockchain method outlined above is permanent and your identity cannot be erased in the case of a regime change.)

Unfortunately, governments and business organisations are (by their nature) fiends for centralisation. So, there is little appetite for this development to happen through a top-down approach.

Such a change or an implementation of a DID system can only manifest from a bottom-up approach where individuals like us demand for a rethink of the entire cybersecurity paradigm and stop throwing our hands up in the air and saying “it is what it is” every time such a security breach happens.

The philosophical underpinnings of a DID system, like the entire crypto industry, is about the willingness to take personal responsibility. It is not a technological silver bullet like what most people believe. It is hard and it is difficult, but it does mean reclaiming your own individual sovereignty.

The alternative, of course, is trade it for convenience and allowing big techs to monetise and control our data.

Dr Eric Lim, Senior Lecturer in the School of Information Systems and Technology Management at UNSW Business School, is the founder of the UNSW Crypto Clinic. He can be reached to comment on the above, or anything related to blockchain, cryptocurrency, decentralised identity and more, at e.t.lim@unsw.edu.au.